by Ted Kardash, Ph.D.

The Spirit of the Healer

In the opening pages of the Pacific College catalog we find a statement titled “The Spirit of the Healer”. It reads in part:

Oriental healers were expected to know eight levels of healing and to become skilled in the Five Excellences. These included techniques of self-development and self defense as well as the tools of one’s trade. Qi Gong, Tai Chi, and meditation were practiced to maintain one’s health and increase sensitivity. “Physician, heal thyself” was the healer’s conviction.

Today there are few words to describe the depth of commitment these masters exhibited. The beauty and achievements they have left behind are a testament to the highest aspirations of humankind.

Thus, within the tradition of Chinese Medicine the healer would strive to be:

- well rounded – being proficient in eight levels of healing and mastering the Five Excellences

- directed towards service – teaching by example

- motivated – exhibiting depth of commitment

- growth-oriented – focused on self-development

The ancient masters realized the healing potential of human energy and saw it as a tool in helping others. They knew of the importance of developing and cultivating this energy, or spirit, to its fullest degree within themselves. This would allow them to become effective and highly skilled practitioners. To “heal thyself” would be to help in healing others.

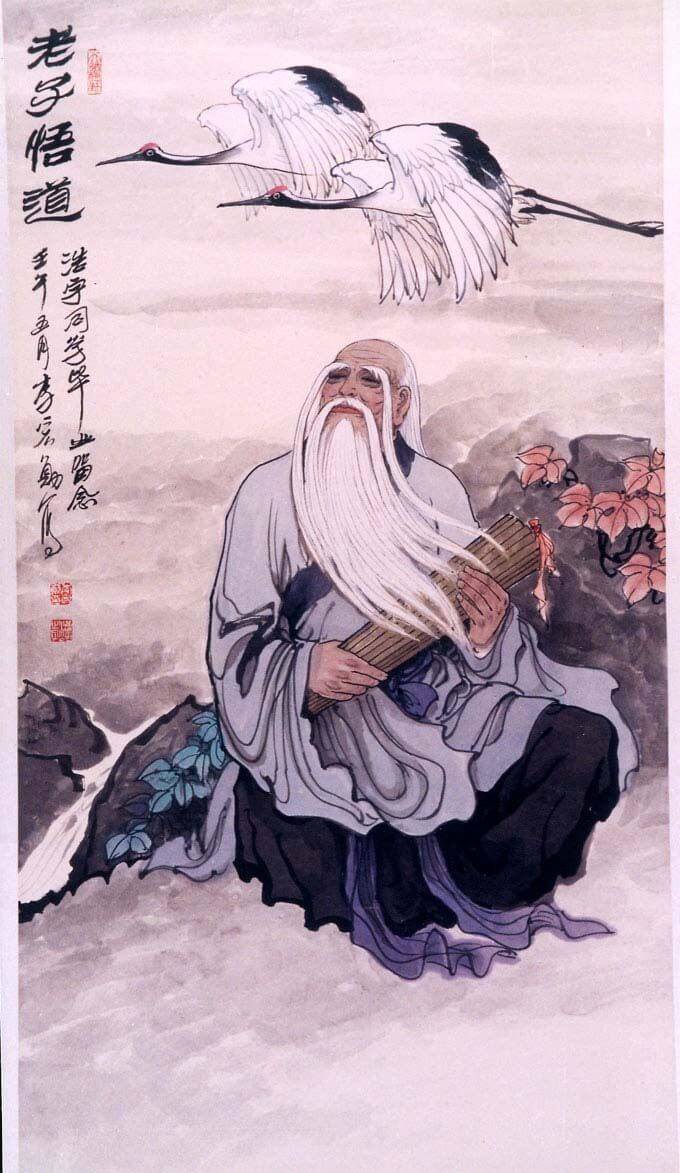

Lao Tzu’s Philosophy on Human Relationships

Traditional Chinese Medicine is based on the core principles of wholeness, balance, and change. These principles are derived from the ancient Chinese wisdom tradition of Taoism and are most clearly articulated in its seminal work and great literary classic, the Tao Te Ching (The Power of the Way), one of the world’s most translated books. This text speaks of the interconnectedness and interdependence of all life, and how humans can nourish one another through adopting certain values, attitudes, and behaviors. Lao Tzu, the legendary Taoist sage regarded as the “author” of this masterpiece, states that there is an essential goodness and trustworthiness to humans, and that these traits can be cultivated and strengthened, both in oneself and in others, through the manner in which we all interact.

As an example, in Chapter 49 of the Tao Te Ching, Lao Tzu states

The sage has no mind of his own,

He is good to people who are good.

He is also good to people who are not good

Because essence is goodness

And in Chapter 67:

I have just three things to teach:

Compassion, simplicity, and patience.

Simple in actions and in thoughts,

Patient with both friends and enemies,

Compassionate toward both self and all beings in the world.

The “sage” is a representation or metaphor for wise behavior, action that leads to harmony and balance and that benefits the greater whole. Lao Tzu is saying that by reaching out to the fundamental goodness and trustworthiness in others, whether these attributes are readily evident or not, we can help foster them and bring them to the fore. We accomplish this by being patient with another’s process, bringing understanding and compassion to our interactions, and behaving in simple and direct ways.

Lao Tzu also commented on those relationships that have a perceived power differential, such as student and teacher, or, of course, patient and doctor. In such “over-under” associations the person in the position of authority often holds an inordinate amount of power while the other is considered to be “less than”. If each person remains narrowly locked into their role, the resulting interaction can become unproductive or even unhealthy. Lao Tzu points out that both persons are essentially equal and have an important and creative part to play in the transaction, that both are equally needed and important for the relationship.

Lao Tzu comments in Chapter 27:

What is a “good” man?

A teacher of a “bad” man.

What is a “bad” man?

A “good” man’s charge.

A teacher must be respected,

And a student cared for.

Therefore the sage takes care of all men

And abandons no one.

The terms “good” and “bad” are used to denote the opposite roles that we play. Lao Tzu urges us to see these roles as naturally occurring opposites rather than moral ones that carry a judgment of right and wrong. One person is not “bad”, or “less than” the other. Being limited by one’s role undermines the experience of connectedness and reduces resourcefulness. The doctor needs the patient as much as the patient needs the doctor. The relationship functions best when both roles are respected and treated with equality.

And finally, form Chapter 66:

If the sage would serve the people, he must serve with humility,

If he would lead them, he must follow behind.

Every teacher can and should learn from his students; every doctor can and must learn from his patients and must be willing to follow their lead at appropriate moments.

Western Psychology and Human Relationships

In our own western culture, we can find an approach to human interaction similar to that of Lao Tzu, both in general terms, as well as specifically relating to the healing relationship. Carl Rogers, regarded as the founder of the Humanistic School of Psychology, outlined its basic principles concerning how a practitioner can help a client:

§ People are essentially trustworthy.

§ Humans have a vast potential for understanding themselves and for resolving their own problems.

§ Humans are capable of growth toward self-direction and contain an inherent tendency to becoming “fully functioning persons.”

§ Prime determinants of the outcome of the therapeutic process are the attitudes and the personal characteristics of the therapist, and the quality of the client-therapist relationship.

§ Therapy is a shared journey in which both client and practitioner reveal their humanness and participate in the growth experience.

Rogers agrees with Lao Tzu that humans are essentially trustworthy and are capable of growth, given proper support. He also states that the characteristics or personal traits of the practitioner, the way in which she expresses herself, her understanding and skill – her spirit or energy – have a great impact on the healing process.

Western psychology also recognizes the importance of relationships to one’s health and well-being. Attachment Theory is a study of the effects of bonding between infants and caregivers. Findings conclude that not only children thrive in supportive and caring relationships, but that adults continue to have the same attachment needs in order to function highly. The experience of a safe, trusting, and secure relationship can promote healthy individual functioning and have a positive overall effect on one’s well-being. This, too, coincides with Lao Tzu’s observation that compassion, support, patience, and kindness elevate others.

And finally, the latest western research in neuro-science, the study of how our brains work, shows that when two individuals are highly attuned, or open to one another, neuronal patterning in the brain is affected and can result in mental, physical, and emotional changes in both parties. If the practitioner’s intent is to be helpful, supportive, and understanding, if his energy or spirit is clear and sufficiently developed, a restructuring in the patient’s nervous system occurs in response, and the effect on the patient can be profoundly positive and healing. This is energy medicine at a very high level.

If you think a career in holistic medicine is something you would like to pursue, contact us and speak to an admissions representative to get started on your new journey!

The Role of the Practitioner in the Healing Process

It seems self-evident that a patient who feels comfortable and safe with her practitioner will be more responsive in treatment – more open to sharing important information; more compliant in following medical suggestions; more willing to express thoughts and feelings vital to her well-being.

In fact, many recent (as well as not-so-recent) studies do show exactly that – a client-practitioner, or doctor-patient relationship, that is marked by a sense of positive personal connection tends to produce more successful outcomes than when there is little or no personal bond between the two persons. It would be desirable, then, to create an appropriately strong and healthy link between doctor and patient as an integral part of treatment.

And what exactly is a healthy, productive relationship between doctor and patient? Based on interviews with both patients and medical professionals, researchers have discovered that certain character or personality traits exhibited by the practitioner can have a very positive effect on the healing process. The result is that ten specific traits, or personal characteristics, have been identified that correlate highly with successful results in treatment. These traits not only provide the foundation for a healing relationship, they also provide a framework for nurturing and cultivating the practitioner’s own energy. They can certainly be seen as an expression of the spirit of the healer.

How does all of this relate to the practice of acupuncture? Many future practitioners are drawn to Traditional Chinese Medicine precisely because of its collaborative quality – the patient is seen as an active participant in the healing process. In order for the patient to communicate openly with the doctor, she must develop trust in the relationship, feel safe, supported, and connected. She is then better able to communicate her own needs, provide accurate feedback on the treatment, and develop insight into her own experience. This allows the practitioner to better understand the patient and to create a treatment plan with the optimum chance of success.

The Ten Practitioner Traits

Cultivating the 10 practitioner traits is the pathway to establishing the healing relationship that is so beneficial to the patient’s well-being. Just as importantly, nurturing these characteristics becomes a part of the practitioner’s ongoing process of self-growth and development so that she comes to embody and express these traits in a natural, authentic manner. In this way, the practitioner herself becomes part of the healing process. She embodies the spirit of the healer.

The first five traits help create an environment where the client can feel safe and supported, trust the practitioner, and feel free to explore his own healing experience.

Empathy

We are all endowed with the capacity to be empathic, to understand another’s experience, whatever that may be, and whether we may ”agree” with it or not. To be empathic is simply to walk in another’s shoes without judgment. Even if we have not had a similar experience, we can understand the feelings involved.

Genuineness

This means to be a real living human being, not getting caught in the role of doctor so that it creates a barrier for the patient. To be genuine means to be open and honest while fulfilling our role in a creative and appropriate manner.

Respect

Carl Rogers described this trait as one of having absolute positive regard for the patient, honoring their process, accepting them for who they are, and respecting their right to make their own decisions.

Warmth

Warmth is a basic physical (food, clothing, shelter), as well as psychological (touch, companionship) need for all humans. It is a natural way of relating. We can be “warmed” by even a stranger’s smile or nod. Studies show that patients seek practitioners who display natural warmth rather than a professional aloofness.

Self-Disclosure

One of the most powerful ways of learning is from one another. We truly teach by example. Patients can benefit by hearing stories of the practitioner’s own struggles and accomplishments when they relate directly to the patient’s own experiences.

The next three traits have an aspect of challenge to them. They can help the patient change and grow.

Immediacy

This is the ability to be fully alert to the patient’s immediate experience and to help them become more fully aware of what they may be feeling or even thinking. Pointing out a tremor in the voice or a clenched jaw may illuminate something important for them.

Concreteness

The practitioner, by paying attention to detail, learns to organize time and information wisely. This keeps the treatment on task and can also help teach the client valuable skills in organization and communication.

Confrontation

We all need to be re-directed from time to time. We tend to deny or ignore painful situations. A skillful practitioner will gently and respectfully help clients face issues that impede healthy functioning.

The last two traits focus on a way of living and developing a deep understanding of who we are as human beings.

Potency

As a practitioner cultivates the various traits, and experiences his interconnectedness with others, he develops an internal strength which is available for healing both himself and helping others. Potency has an attractive quality and draws those in need of help toward him. This trait also has the effect of helping others find and develop their own potency.

Self-Actualization

Lao Tzu uses the term “Sage”, a wise being, to describe action that arises from our highest potential and meets the need of the moment. Often, when one is focused on the requirements of others, or is in a state of compassion, or is deeply experiencing connection with the patient, that natural wisdom emerges, and one says or does “the right thing”, what is necessary for change to occur.

Client and practitioner – a shared journey

The goal of Traditional Chinese Medicine is to harmonize and balance one’s energy or spirit. The practitioners of old realized that human energy, by its very nature, has a healing quality. They knew the importance of cultivating and refining their own energy and the role this energy played in helping their patients attain good health. To truly help balance another, one must himself be balanced. To achieve this state, the ancient masters developed various techniques that continue to serve us to this day.

And through our own contemporary cultural experience, we add other tools and approaches to refine our own energy and develop the Spirit of the Healer. One such way is through the practice of the 10 traits, which can serve to liberate our healing energy and connect us deeply with others. We learn to see the goodness in all, including ourselves. We learn respect for each other’s path. As imaginary or unnecessary boundaries between individuals dissolve, we discover our common unity and see that we are all in the process of healing, changing, and growing. Patient and practitioner help one another. Carl Rogers states that healing is a shared journey in which client and practitioner reveal their humanness and participate in the growth experience. Lao Tzu states that the sage is compassionate toward the self and all beings, takes care of all, and serves with humility.

Ten Traits

- Empathy – understanding our patient’s experience without judgment

- Genuineness – being authentic, sincere, honest, and spontaneous

- Respect – showing unconditional positive regard for our patients and honoring their potential

- Warmth – conveying acceptance and caring through non-verbal behaviors such as eye contact, smiling, touch, and body language

- Self-Disclosure – sharing our own experiences with a patient when it is helpful to their healing process

- Immediacy – staying alert to a patient’s unspoken or suppressed thoughtsand feelings which may be affecting their healing process

- Concreteness – helping the patient to remain focused and specific so that information is gathered efficiently and respectfully

- Confrontation – supporting the patient in perceiving incongruence and inconsistency in their own experience

- Potency – making conscious use of our own personal power to help empower our patients

- Self-Actualization – wisely recognizing and participating in the ongoing process of change and growthwithin both our patients and ourselves

References:

Lao Tzu. Tao Te Ching. (Feng & English, Trans.). New York, Vintage Books, 1972

Jacquelyn Small. Becoming Naturally Therapeutic – a Return to the Essence of Helping. New York, Bantam, 1981.

Bowlby, John. A Secure Base – Clinical Applications of Attachment Theory. New York. Routeldge, 1988.

Rogers, Carl R. On Becoming a Person: a Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961.

Featured Posts: